Please do not disturb

Just like regular operating systems, embedded OSes have multiple responsibilities. First, they have to execute user programs. And second, they need to manage IO. IO usually doesn’t execute instantaneously, it takes some time. Some time we’d rather spend executing user code rather than just waiting for IO to complete. The external devices are usually smart enough to run on their own and just interrupt the compiler when they need something. So, upon an IO request by a thread, we just initiate an IO operation on the hardware and block the thread until IO finishes. If there are other threads to execute, we’ll just do that.

However, interrupts act like preemptive threads. Meaning, at any point in a program, we might get preempted by an interrupt service routine. Although ISRs and the normal thread world should be as decoupled as possible, at some point, some data will be shared between them. This easily leads to difficult to track down race conditions.

The most obvious resource ISRs and the normal world share is the thread queues. There’s a queue of runnable threads in a system that the scheduler uses, called the run queue. When a thread is created, it’s placed on that queue so it can start executing. When a thread starts executing, it’s taken off that list. When a thread blocks, it’s placed in the wait queue of whatever it’s blocking on. The threads in a block queue is usually placed back into the run queue by an interrupt service routine. For instance, when you’re sleeping for 5 seconds, you’re waiting for an ISR to wake you up by placing you back to the run queue eventually.

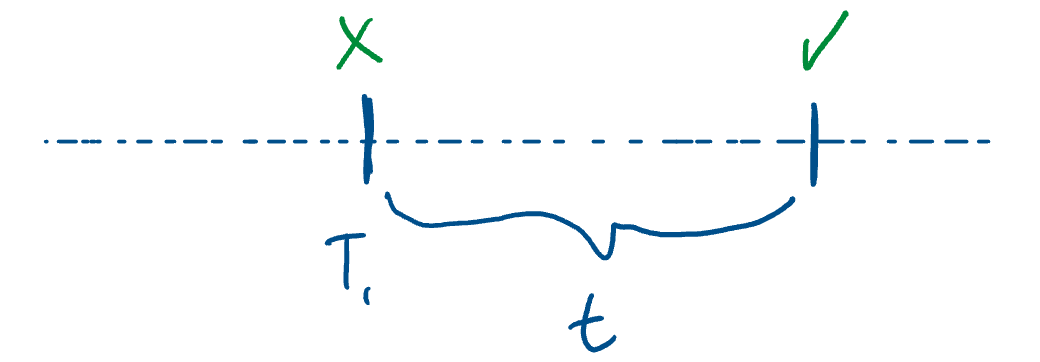

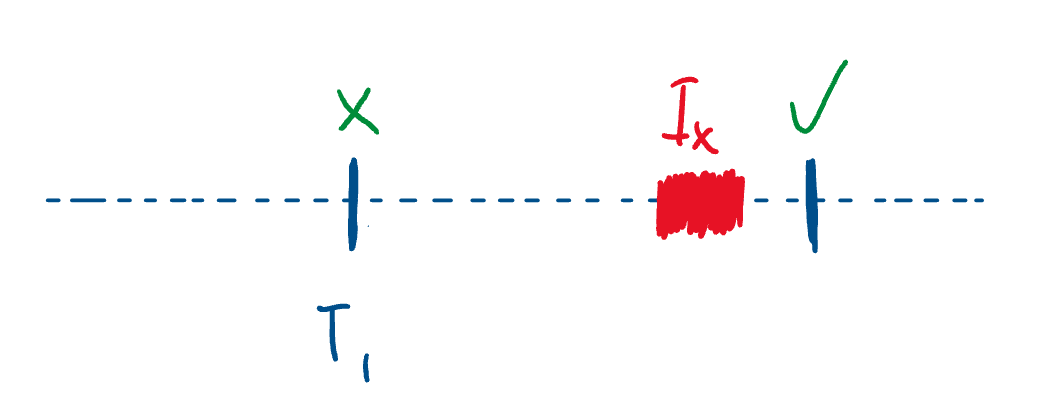

Now, imagine a moment where a task starts attempts to block on a resource, called at time and it takes time to finish placing the thread in the block queue and suspend it. There exists an ISR that unblocks threads waiting on .

It is possible that will be serviced during . In that case, we’ll have a nice race condition and quickly go into the undefined behavior land.

To avoid such a problem, we disable interrupts before placing a thread in the wait queue of a resource and enable them back right after placing it in the queue.

Death by a thousand interrupt disables

That solves our little problem. However, it turns out that you don’t want to always block unconditionally. You want to check if a condition has been satisfied and if not, block until it does. This is exactly what a semaphore represents:

semaphore bytes_received{0};

ring_buf<char, 32> bytes;

char read_byte(){

bytes_received.down();

auto f = bytes.front();

bytes.pop_front();

return f;

}

When read_byte is called, we don’t necessarily want to block. If there already exists some bytes in the buffer, we want to take the first one. If there’s none, we want to wait until some arrives.

Now, to check how many bytes there are in the buffer, we have to read a shared integer. To do so, we must disable interrupts. This is in the down function of semaphores, and looks like this basically:

void semaphore::down()

{

int_guard ig;

if (--count < 0)

{

m_wait.wait();

}

}

Now, we disable interrupts once in the int_guard. Then, we call wait on the m_wait object, which is of type waitable. waitables are basically just a wrapper around a queue of threads that present an easier interface, like a wait function rather than emplace_back(current_thread) and suspend.

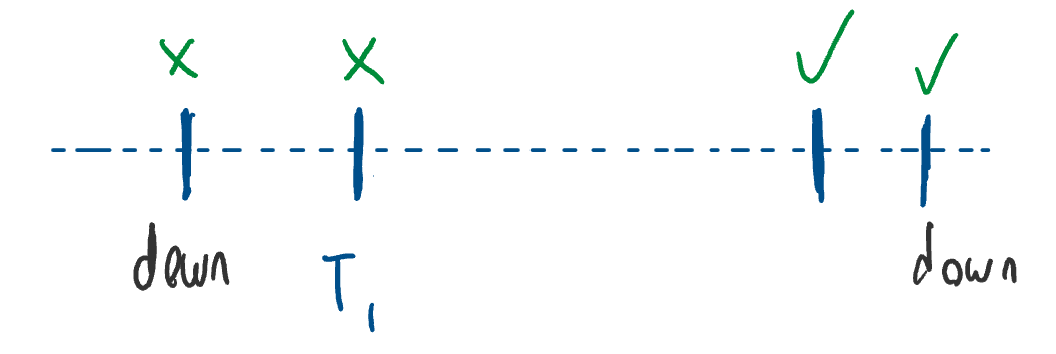

But, as we talked about previously, blocking also needs to disable interrupts. So, it’ll construct another int_guard object before placing the thread into the wait queue.

After that, we have to suspend the current thread, which means switching context to another thread. However, context switching is another potentially dangerous function. So interrupts must be disabled during that time as well.

So, for just a semaphore::down call, we have to disable interrupts 3 times. This is called the abstraction penalty. Since we obviously don’t want to pay this cost, we’ll cut some corners in terms of safety. For instance, the last call, suspend_self will have a precondition:

/**

* Gives control of the CPU back to the scheduler,

* suspending * the current thread.

* If the interrupts are not disabled when this function

* is called, the behaviour is undefined

*/

void suspend_self();

// pre-condition: interrupts must be disabled

So, we’ve just traded performance for safety. Now, our code has UB if we attempt to suspend the current thread without disabling interrupts. Now, this function isn’t meant to be called directly, so the dangers aren’t that high, but still, there’s some unsafety and we still call the interrupt disable/enable pair twice.

You might be wondering how we can actually disable and enable interrupts twice. The hardware doesn’t know how many times you’ve disabled interrupts after all. There are 2 ways you can go about that: either store the current interrupt information in the int_guard object and restore it upon enabling, or count how many times we’ve disabled interrupts, and only enable them back when the counter reaches 0. The former solution is more pure, but the latter has $O(1)$ storage cost, so that’s the way we go about it. However, either method imposes some non-trivial runtime overhead, so I’d rather not to that twice.

Ideally, I could mark functions as no interrupts like we do with const or noexcept:

void waitable::wait() no_int;

void suspend_self() no_int;

And the compiler just statically checks whether I’m calling from a non-interruptible context. However, this doesn’t scale as I can just come up with more stuff that fits this criteria.

The solution is to use the type system. We’ll introduce a new empty type, and make int_guard inherit from that:

struct no_int {};

struct int_guard : no_int { ... };

And we’ll change any function that expects there to be no interrupts to take a const reference to a no_int:

void waitable::wait(const no_int&);

void suspend_self(const no_int&);

Now, the C++ compiler will just prevent anyone from calling these functions unless they have an int_guard instance lying around.

And waitable::wait just passes it’s reference to suspend_self, so it’s easy to carry this information down the call stack.

So, semaphore::down will just look like this:

void semaphore::down()

{

int_guard ig;

if (--count < 0)

{

m_wait.wait(ig);

}

}

If you aren’t familiar with C++’s inheritance mechanism, this doesn’t add any overhead to functions the compiler inlines. If it can’t inline, it’s equivalent to passing a single reference.

Awesome! Now, you might say they can just construct a no_int instance and pass that as well. Well, they shouldn’t. But we have the technology to solve that as well:

struct no_int {

private:

no_int() = default;

friend class int_guard;

};

This way, short of modifying the no_int type, the users of the library must use an int_guard.

There’s another

You might be wondering why we’re going to unnecessary lengths and not using a const int_guard&. The answer is that, there’s another way of disabling interrupts in a system, and the other one is if we are already in an interrupt context (that means we’re already servicing an interrupt)!

To model this, we add another type:

namespace detail {

struct int_ctx : no_int {};

}

When we enter an ISR, we’ll construct an int_ctx, and pass that to the functions that expect interrupts to be turned off.